Operationalizing Positive Reinforcement Training

The animal training world is full of jargon and “Positive Reinforcement Training” is no exception. It usually entails a lot of other concepts as well including clicker training, bridging stimulus, operant learning, cues, reinforcers, antecedent arrangement, etc. etc. Being in the positive reinforcement community myself, I can also tell you that there is a wide range of skills and knowledge among positive reinforcement trainers and how we put the science into practice. There is never just one way to train a behavior and there is an art in behavior change procedures that is unique to each trainer and training session. In the sea of concepts that can feel really abstract to the average pet owner, as well as a variety of trainers to choose from, I thought it would be useful to tease out some of the terminology into measurable observations and shine a light on what working with this positive reinforcement trainer actually looks like for you and your pet.

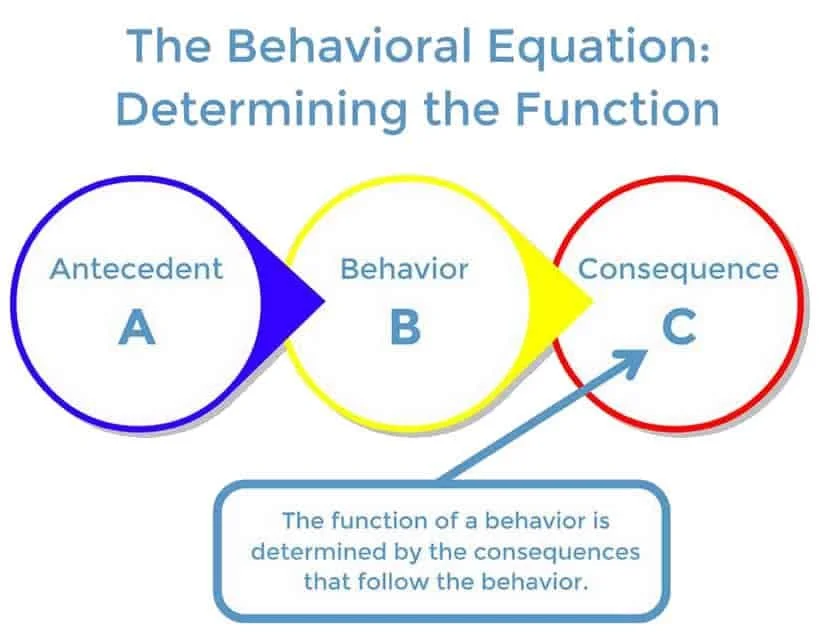

First, let’s break down positive reinforcement. Think of positive like addition. Something is added to the environment. Reinforcement means that future behavior repeats or increases as a result of the consequence. In other words, we’re adding something valuable as a consequence to behavior that is worth behaving for again.

Side note: when I say consequence, I don’t mean:

What I do mean is:

For some reason there aren’t any functional assessment memes as exciting as the consequence meme. Weird, right?

Positive reinforcement lives in the consequence realm. It occurs after behavior. If the behavior repeats or increases, then we know what was added to the environment was reinforcing, or we could call it a reinforcer.

Training aside, positive reinforcement is actually just a natural science. It’s as real as gravity. We all behave to gain reinforcers. Comedians repeat jokes that get a lot of laughs. Babies repeat facial expressions that get encouraging reactions from their parents. Dogs learn to offer “puppy dog eyes” to get their owners attention at the dinner table. Cats rest in sunny spots to gain heat. We work for our paychecks which give us access to a multitude of reinforcers including food, water, shelter, heating, cooling, novel experiences, and more.

Since animals are already behaving for reinforcers, it only makes sense to use reinforcers for training.

Shaping behavior entails taking a goal behavior and breaking it down into small approximations that get the animal closer to the end goal. Small approximations are like baby steps. You have to learn how to crawl before you can walk before you can run kind of thing. You can reinforce small approximations with a bridge (such as a clicker) and a treat your animal will work for.

Let’s break down clicker training. Clickers are nice because they have such a distinct sound. A clicker on its own is absolutely meaningless. But when that click noise is paired with a bite of cheese or chicken or some other treat your pet loves, it gains significant value after only a few repetitions. This is similar to the sound of a can opener gaining meaning after it’s paired with the can of tuna that your cat loves. Or your key turning in the door predicts your dog’s person coming home. The pairing of a click and a treat makes a clicker go from meaningless to meaningful. The click tells your pet “a treat is on the way.” I love seeing a dog learn this for the first time because their tail starts to wag when the association is made.

A click timed precisely with behavior tells your pet “that behavior is worth repeating because a treat is on the way.”

A clicker is just one example of a bridge, or bridging stimulus (think: bridging the gap of time between behavior and receiving the reinforcer). You can also use a whistle, the word “good” or “yes,” a flash of light, your hand moving to the treat pouch, a hand signal, and many more. I choose my bridge based on the circumstance such as how close I am to the animal, what their perspective looks like during the training session, the environment around us, the behavior I’m shaping, or where I need to place my hands while teaching. As long as the bridge means “good job a treat is on the way” and the animal understands the message then we are all good.

An example for selecting behavior in small approximations and arriving at an end goal could look like:

Goal: Dog spins in circle

Prerequisite skills: Follow trainer’s hand

Bridge and reinforce the animal’s behavior for the following approximations:

Trainer present hand a couple inches away from dog’s nose. Dog touch nose to hand.

Trainer present hand a few inches away from dog’s nose. Dog touch nose to hand.

Trainer present hand a few more inches away, dog touch nose to hand.

Trainer present hand on opposite side, a couple inches away. Dog touch nose to hand.

Trainer continue to present hand at varying distances and locations, bridge when dog touches nose to hand.

Once the dog is going towards the hand reliably, start presenting your hand off to the side/slightly behind the dog to begin prompting for a spin. Bridge when the dog is moving towards the hand, not just touching their nose to the hand. (We want to select movement now to gain momentum)

In small increments, trainer move hand further and further around until the dog is following in one big circle, starting and ending in the same position.

At the last step, the dog will have the behavior complete, but the prompt is still really big. The next approximations can be all about fading out the prompt, or making the prompt gradually smaller. That could look like the big circular motion turning smaller and smaller and smaller, all the way until you just cue the behavior with the flick of a finger. The end cue is up to the trainer and their preference. The ultimate job of the cue is to provide information to the animal that if they spin, then they will receive a reinforcer. Just like the association between the bridge and treat. The cue predicts the reinforcer and the bridge predicts the reinforcer.

Behavior isn’t just seeking reinforcers, it’s also seeking predictors of reinforcers.

Now that we are talking about cues and prompts, we aren’t just living in the consequence realm anymore, we’ve moved to the antecedent: the immediate environment before behavior occurs.

Like I said in the introduction, there is an art and science to training, and I’ve always seen the art in the antecedent. The prompting, the cueing, the timing of both in relation to what the animal is doing, adjusting my prompt to give the animal the clearest idea of how to get the reinforcer, adjusting the environment to set the animal up for success. The antecedent contains information.

Two way communication is mostly present in the antecedent as well. In the training plan, I set specific distances for the hand placement, but if the dog doesn’t do the behavior I was looking for, it’s on me to adjust my communication, like providing a shorter distance the next time. I also chose a dog for this example because they use their nose to investigate the environment, but if it was a parrot I was teaching, I wouldn’t necessarily expect them to offer placing their beak on my hand in just the first step; they might have a different prerequisite skill to learn. Or, if it was a fearful dog who shies away from hands, I would approach with much more sensitivity, maybe targeting their nose to something else in the environment first or using a different shaping plan altogether.

Shaping for a spin is just one example of training a behavior with positive reinforcement. The concept can be applied to any skill that the animal is physically capable of doing. Some training plans are up against a previous learning history that can take more time, others involve much more thought to the environment to reduce errors during learning, but all are catered to the individual animal you are working with. No training plan is set in stone. It’s always an ever evolving dialogue, and the learning doesn’t end just because you’ve reached the last approximation. The reinforcers can also be faded out from treats to naturally occurring reinforcers, depending on the behavior, but also knowing that our cue is only as strong as our reinforcer.

Positive reinforcement training is a fun way to connect with your pet, learn new skills, and teach alternate skills to any behavioral issues that are going on. If you find yourself asking, “how do I get my animal to STOP…” instead ask what you want your animal to do instead and shape it. You can also get an idea about what they are working for and use that as a long term reinforcer (just because it’s a problem for you doesn’t mean it’s a problem for them). Like if your dog is jumping for your attention, you can shape a sit with duration using treats and then use the attention they were working for as a reinforcer once the new skill is fluent.

With positive reinforcement training, I’ve taught a grizzly bear to present his back for a voluntary mass biopsy, a mountain lion to lay still on his back for abdominal x-rays, a tiger to open his mouth for dental checks, dogs to give me their paw for nail trims, domestic cats to voluntarily crate and let the door close, a leopard to roll over, and so on, and so on. The possibilities are endless and no species is excluded from the art and science of training.

Learning how to train animals is a skill with many nuances that takes time and practice, just like the behaviors our animals learn, and some behavior can be more complex than others. Hiring and consulting with a trainer who has experience on the subject is usually the best place to start, especially for the fastest results. With the right trainer, you can feel like Dr. Dolittle in no time and build a beautiful bond and relationship built on trust and shared reinforcers with your pet.