Let’s Talk About E Collars

My thoughts? We can do better.

You may have heard about E Collars from a list of training tools on a dog trainer’s website, or maybe you saw a shock collar sitting on the shelf at a pet store promising results on the package. Maybe you’ve even heard whispers from friends talking about less aversive collars that only spray a scent or only send a slight vibration, and they assure you that it really works! At best, they do work. When an aversive stimulus is timed with behavior precisely, the animal will stop the behavior. The person on the other side gets this feeling of voila – fixed.

No more barking. No more jumping. No more getting up on the counter. At worst, the aversive is more abusive than punishing, the dog learns to tolerate pain in order to gain what they are behaving for, or your dog faces the detrimental side effects from the use of aversive stimuli.

When we talk about E-Collars, and all of their collar cousins, what we are really talking about is the use of positive punishment (P+) in a behavior program. When we break it down, positive means we are adding (+) to the environment and punishment (P) means future behavior decreases. A useful example could look like: when someone walks past the front window, the dog barks, and an uncomfortable vibration is delivered around the neck. We could predict that the next time someone walks past the window while the dog is wearing the collar, the barking will decrease or stop altogether.

A word of caution: when using an aversive, there is a fine line between unnecessary pain and not aversive enough. In order for a punisher to be effective, it should only need to be used once. If an aversive is being repeated and future behavior is not decreasing, then it is no longer punishment by definition. It’s abuse.

But for our example, let’s say we’ve got the perfect level of discomfort, and the barking does stop.

What will the dog do instead? Well, it depends… why was the dog barking in the first place?

We have to look at the function of the behavior. Ask yourself, “WTF?” (What’s the function?) and break down the barking behavior in relation to the immediate environment. What prompts the barking? What is added or removed as a result of the barking? Applied Behavior Analysis calls this method a functional assessment, using the ABC unit:

Antecedent (environment): Person walks by front window

Behavior: Dog barks

Consequence (environment): Person is removed

Prediction: The next time someone walks past the front window, the dog will bark

So we know this: the dog does not want people to come near the house and barking is effective for removing them. It’s communication. The duration and intensity of the barking is all selected by this one consequence: the person is removed. Every. Time. The mailman drives away, the jogger turns the corner, the Amazon guy walks back to his truck.

Now, with this collar, barking doesn’t work. The new consequence to barking is a zap, vibration, gross smell, etc. What predicts this consequence for the dog? Someone walking by the window. Fill in the ABC units: Person walks by > Bark > zap.

So what will the dog do instead? The side effects to an aversive strategy include escape/avoidance behavior in response to the stimulus. You may see increased aggression. Apathy and over generalized fear have also been documented. It’s hard to say exactly, but you could expect avoiding the window, avoiding that level of the house, hiding, biting, growling, or trying other behaviors that may “remove” the person. We could guess that the dog dislikes people walking by even more than they did before with the pairing of an aversive. If the dog is not wearing the collar, I would predict barking would come back with vengeance. Punishment does not address the function of the behavior nor does it teach the animal what to do instead.

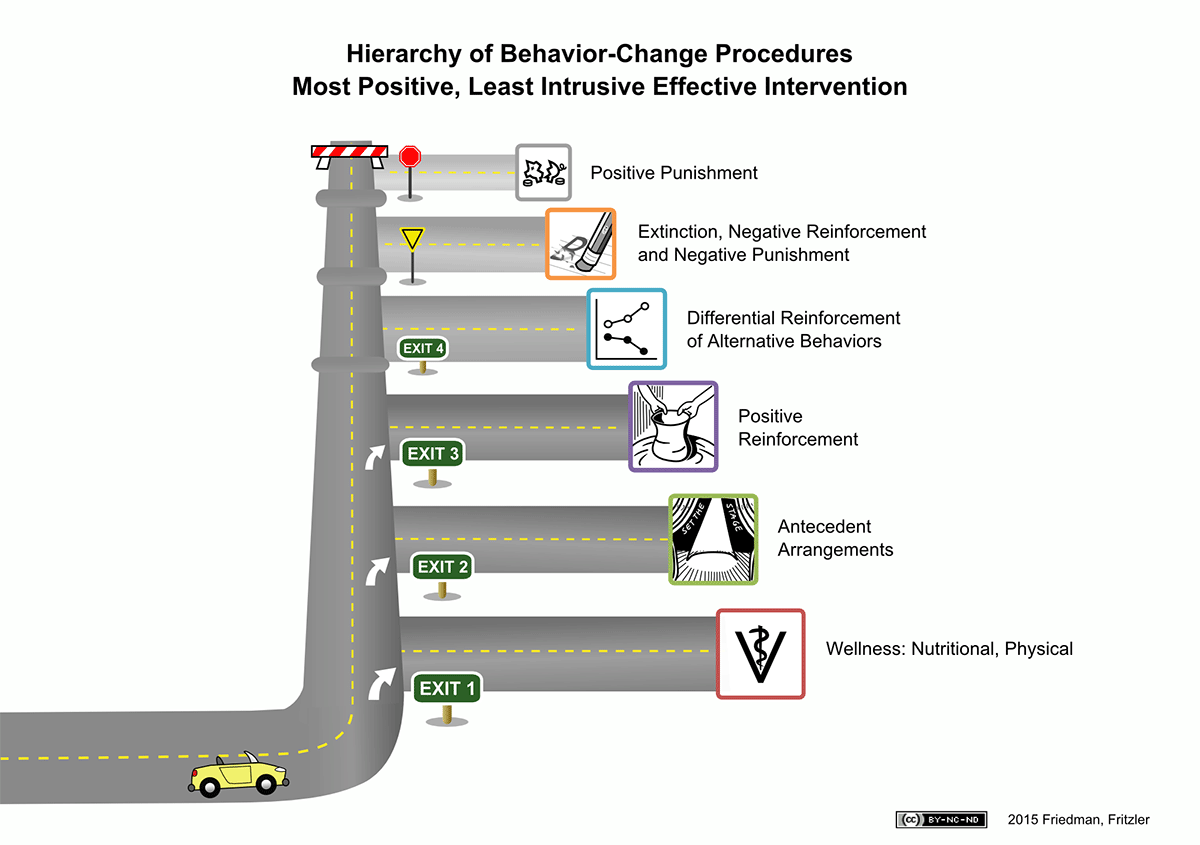

Using aversives to punish behavior is the ultimate loss of control for an animal. These collars tend to have their own hierarchy from least aversive to most aversive, but that isn’t the hierarchy we should be looking at as a first stop. Instead, let’s look at Dr. Susan Friedman’s Hierarchy of Behavior Change Procedures:

You can look at this hierarchy as a means of giving the animal as much control in the environment as possible in the early exits. Every speed bump and sign along the route is a decreasing level of control. After all, control is a primary reinforcer for behavior. Primary reinforcers are not learned, they are innate. Other primary reinforcers include food, water, and shelter.

Notice how punishment is all the way at the end? After multiple speed bumps and signs?

Punishment should never be the first stop in a behavior change procedure. Ruling out health issues, setting up the environment to make the undesirable behavior less likely and the alternative behavior more likely, and teaching the animal what to do instead is usually all that is necessary for success. We should only move forward after careful consideration, documenting our attempts, and utilizing all of our resources.

We know that the person walking by the window will disappear whether the dog barks or not. The dog is healthy, the environment could use some tweaking, and a new skill can be shaped in small approximations, adding value to the consequence instead of an aversive. Bonus: if a person walking by has enough positive experiences associated, the dog may even look forward to seeing someone walk by, eliminating the barking function altogether. The only side effects here will be a wagging tail.